When psychosis sets in: A review of Maniac 1934

What happens when you adapt an Edgar Allan Poe story and combine it with contemporary attitudes of exploitation, if only to create a film which looks like a graduate school teaching tool? “Maniac” from 1934, directed by Dwain Esper and written by his wife Hildagarde Stadie, is the culmination of such a description, even if the entertainment quality in the film has greatly diminished, compared to most films from the 1930’s. Even though exploitation films date as far back as the 1920’s during the silent film era, it was the pre-code 1930’s which explored venturing into the dark recesses of cinema. Since both “Maniac” and Esper are little known compared to the most popular exploitation film of that time, “Freaks” (1932), directed by Tod Browning, it is worth investigating the appeal of “Maniac”, the story itself, and why it would be considered as a classic textbook case of mental illness in the twenty-first century.

“Maniac” opens with a preamble in textual form from Dr. William S. Sadler, director of the Chicago Institute of Research and Diagnoses. The viewer is introduced to a world where a reasonably sane person falls into the depths of psychosis which includes forms of dementia, paranoia, and manic depression. The movie is about a former vaudeville performer named Maxwell whose expertise is in doing impersonations. He is also a wanted man by the authorities, but as to what charges he is wanted for is not disclosed to the viewer; perhaps that information is not necessary, given the nature of the plot as it unfolds.

“Maniac” opens with a scene of two men sitting at a table conducting an experiment in a laboratory: Horace B Carpenter in the role of Dr. Meirschultz, and Bill Woods in the role of Maxwell seated adjacent to him. Carpenter, with his wild shock of gray hair, beard and horn-rimmed glasses, looks every inch the proverbial mad scientist as he holds a large hypodermic needle in his hand with his back to the camera as he speaks to Woods. Carpenter describes his intentions to perform the experiment on a human guinea pig, which is the reanimation of a deceased person. Woods expresses his gratitude towards Carpenter in taking him under his wing and providing protection from the authorities, but the slight, wavy-haired young impersonator draws the line at what Carpenter plans on doing. Carpenter realizes that the decedent he procures must not be someone who will be claimed. The ideal place to get a body nobody would claim is at the morgue, and of course the ambitious scientist is next seen at this location. Gothic and dark in appearance in every way, from the narrow stone stairs leading down into the basement to the large arch visible to the right in the morgue, are a number of mortuary stretchers. Each stretcher has a body covered with a white sheet, somewhat equally distanced from each other. The embalmer, John P. Wade, shows one decedent to Carpenter, a lovely young woman who remains an unidentified actress. She is carried back to the laboratory for the Frankenstein-style experiment.

Yet one thing factors in repeatedly throughout the story: cats. Cats catching mice in the morgue, cats fighting as Woods attempts to steal the decedent of a gangster, cats hanging around Carpenter’s house outside, and his own black cat named Satan. The actual story only begins to pick up when Carpenter exhorts Woods to commit suicide so that the doctor can bring him back to life when the tables are turned – meaning Carpenter is the one who is shot dead – and madness sets in the mind of Woods as he calculates taking the dead doctor’s place.

Woods suddenly hears the front doorbell ring, which he answers. The visiting guest happens to be a client of Carpenter, whose wife is telling Woods that he needs help. Phyllis Diller plays the character of Mrs. Buckley, and her husband, played by Ted Edwards, suffers from schizophrenia. Diller describes how Edwards thinks he is the orangutan murdered in Edgar Allen Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue” story. Diller leaves Woods in order to fetch her husband, while Woods comes up with a plan on fooling her. As Woods uses a nearby makeup kit sitting on the floor in the lab of Carpenter’s house, he slowly transforms his appearance to look like the doctor: cutting off sections of his hair and using spirit gum to form the beard, and hair dye to turn his hair gray. In an attempt to help Edwards after explaining that Carpenter is temporarily gone, Woods administers what he thought was plain water in the hypodermic needle to Edwards. The shot results in some shocking effects, which befuddles Woods. The young girl which Carpenter brought back from the morgue finally comes to life and enters through a door hidden behind an elegantly painted screen, to which Edwards picks her up and carries her off into the night.

Woods fully enters Carpenter’s world when he encounters an eccentric neighbor who keeps a substantial number of cats in cages in his backyard. One of the cats got loose and begins to hang around Carpenter’s house. The neighbor, another unidentified actor, questions Woods on the whereabouts of his lost cat, thinking it fell prey to one of the scientist’s strange experiments. Soon the movie enters the stage where similarities to Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Black Cat” fall into place. Completely caught up in his new identity, Woods suddenly remembers one thing in his life which he completely forgot: his estranged wife.

Alice Maxwell, played by Thea Ramsey, is a showgirl, and with three other showgirls, Jenny Dark, Celia McCann, and Marvelle Andre, are seen in a hotel bedroom. Dark is taking a bath in the bathroom off the bedroom with the door open, kittenish Alice claims she should have the right to bathe first, and the other girls start to banter. Unfortunately, the Mexican-born McCann’s helium-voice is off-putting to the point of being cartoonish. It is a particular newspaper article read by one of the showgirls which prompts Ramsey to seek out her husband and reunite with him. The complete unraveling of Woods speeds up as he goes into full-blown narcissist mode, as the movie depicts women in seductive poses at which he fantasizes about, up to the inevitable Edar Allan Poe ending.

Released two years before “Reefer Madness” (1936), another exploitation film which Esper produced, “Maniac” is a linear story with few pacing issues and gives the appearance that it was intended for the live theatre as compared to film. At several points throughout the movie, superimposed images of hands, scenes from hell, and archive footage of the actor Bartolomeo Pagano as Maciste upon Woods depicts the mental decline he is experiencing. Not only does the serum promote the state of psychosis in Woods, but he also develops narcissism, especially during the fantasy lovemaking scene. Text is used, containing primarily quotes from professionals in the mental health industry.

Probably the most interesting cast member is Phyllis Diller; not the famous 1960’s-90’s television comic personality, but an actress with only two credits to her name: “Maniac”, and one silent film from 1920, “Over the Hill to the Poorhouse”. Like her namesake, she manages to inject substance in her role as Mrs. Buckley, while the roles Horace B Carpenter and Bill Woods play are very two-dimensional. Made on a budget of $5,000.00, “Maniac” is a movie ahead of its time, perfectly suited with exploitation films like “Blood and Roses” (1960) and “Blood Feast” (1972). As a result, “Maniac” holds its appeal primarily for fans of exploitation movies, but on the other hand, also appeals to an audience interested in films which explore psychosis in human nature.

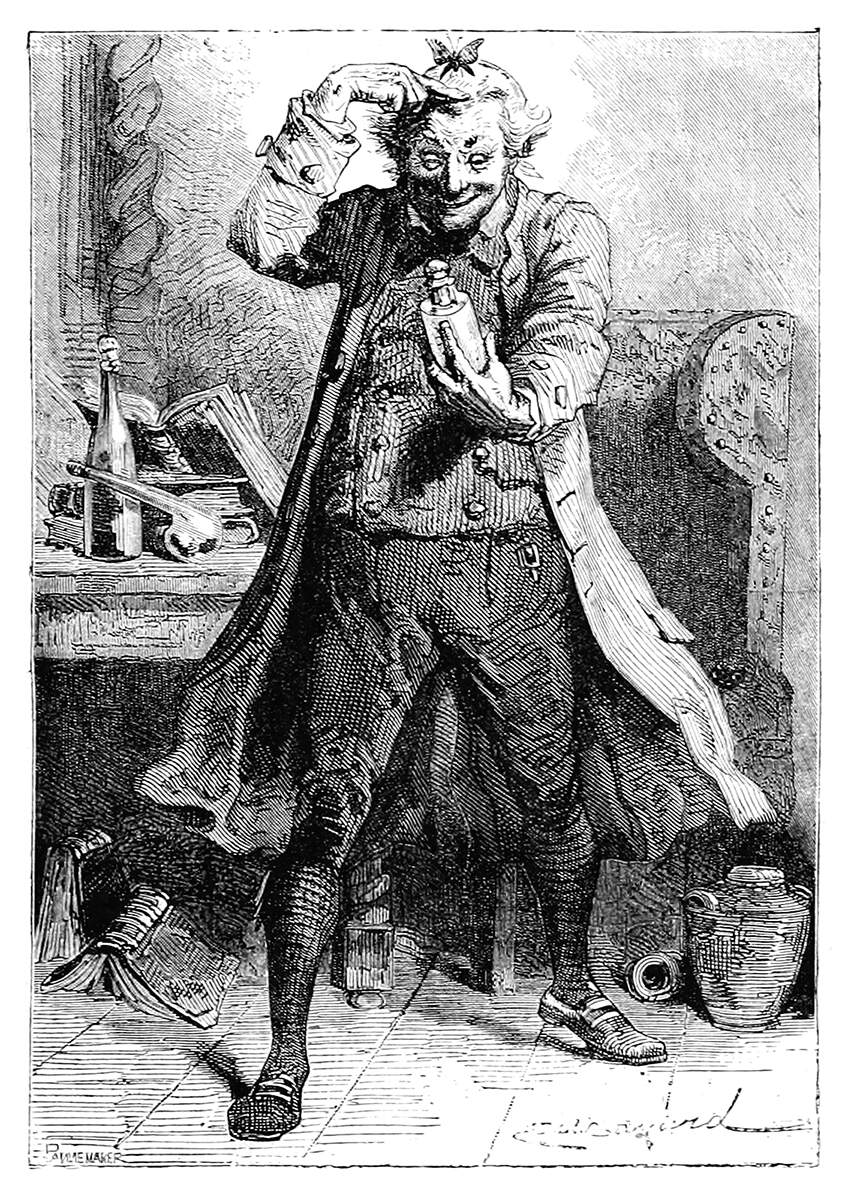

Credit: Illustration by Émile Bayard (1837-1891) from the book “Contes et romans populaires”. Authors: Alexandre Chatrian and Émile Erckmann. Paris: Hetzel, n.d. Old Book Illustrations.