The House at the Bottom of Gardner Lake in Connecticut

Tucked away in a picturesque corner of southeast Connecticut is a natural body of water named Gardner Lake. Bordering the towns of Salem, Montville and Bozrah, the southern part of the lake is home to a state park, almost ten acres in size, where recreational activities include swimming, boating and fishing. On the eastern portion of Gardner Lake is Hopemead State Park, with hiking trails, fishing, and birding. The lake is certainly large enough for these two parks, including what is also Connecticut’s tiniest park, a small island located off the eastern shore close to the southern part called Minnie Island State Park, measuring 0.88 acre in size. As tranquil as the location sounds, Gardner Lake has a rather unusual history, and not because it was named after the family which owned a sizeable chunk of property in the area. Rather, Gardner Lake, almost resembling the chess piece the Knight in shape from a certain angle, is famous for being known as the lake which has a house at the bottom of it.

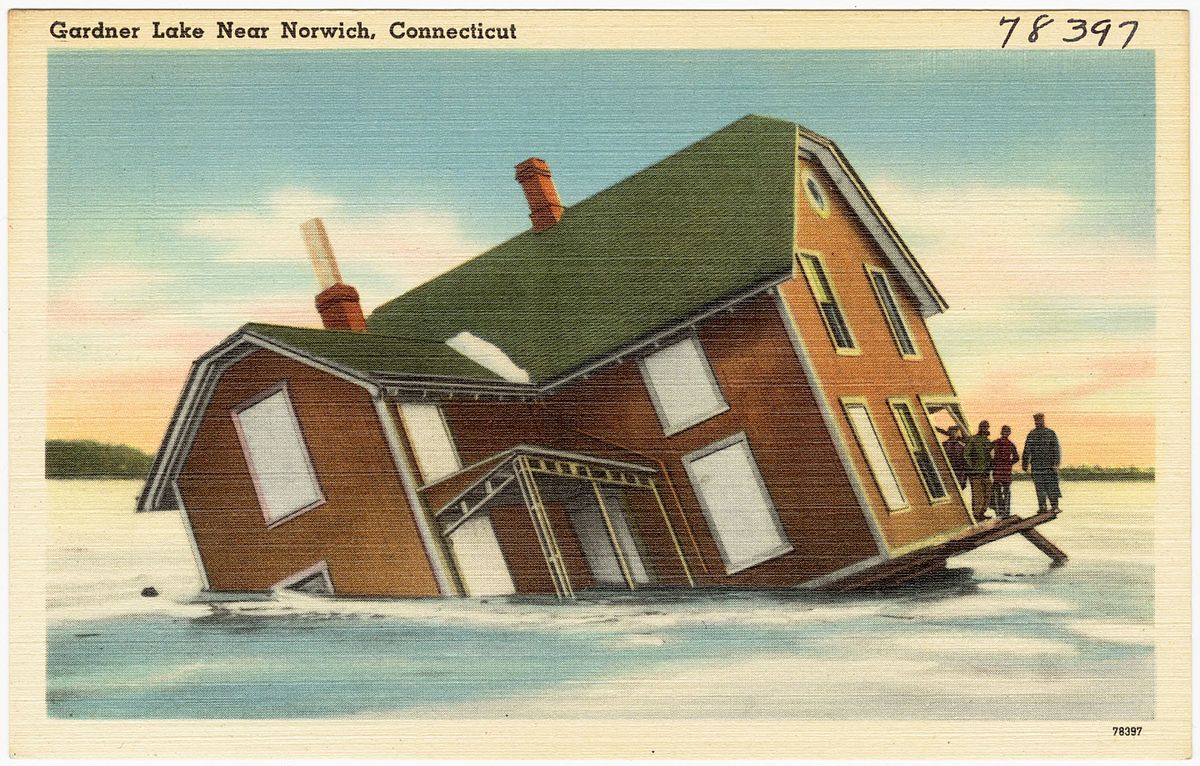

The story dates back to the morning of February 13, 1895 when a local businessman by the name of Thomas LeCount made, what he thought at the time, was an ingenious decision to relocate his two-storey lakeside house from one side of the lake to an adjacent side. In an article from the New London, Connecticut newspaper The Day dated August 25, 1976, LeCount was a grocery store owner from Niantic. His intention was to have his summer home moved from the south shore of Gardner Lake to its eastern shore, which at the time was newly purchased land. LeCount established the logistics of the operation, getting together a team of men and twenty-four work horses to move the house across the sheet of ice which covered the lake on the cold winter morning. Everything was going fine until his house suddenly started sinking into the water, 250 feet from the southern shore, heading towards the eastern shore. The west side of the house sank into fifteen feet of water which is the depth for the majority of Gardner Lake, tilted at an angle with two feet of the house under water while the east side of the house was stuck in the air. While the team of men who helped guide the horses across the lake attempted to get the house upright, they were unsuccessful. According to residents who took part in the spectacle later reported that the half-tipped house remained visible in the lake, until its final deterioration over the decades.

Unlike the modern-day practice of moving a house or other building, which usually requires dismantling it and removing all furniture and carpeting inside, LeCount wanted everything to remain intact for the move. But due to the weight of the house, which was originally calculated to be twenty-eight tons in weight, according to another article in The Day, February 16, 1895. Not surprisingly, it was the kitchen chimney which caused the house to sink the way it did, being considerably heavy.

LeCount may have been good at business, but not the best at moving buildings, for he had also planned to move his barn and bathhouse in the same manner, according to the same article in The Day. With the house slowly sinking into the lake, however, what could be removed relatively easy was: small pieces of furniture, smaller objects like kitchenware and bric-a-brac. The piano remained in the house, and for many years after became a source of folklore that would haunt the locals and anyone interested in being fascinated with the mysterious. This was mainly due to music emanating from the piano underwater with no coherent explanation. Was it due to the numerous fish brushing up against the instrument’s keys? Was the music from Thomas LeCount himself, who loved his summer home so much he wanted to have a better view of the lake from the front window? Or was something else causing the piano to play erratically?

It is unknown how LeCount’s team figured that the ice was sixteen inches thick and “safe” to move a stationary load like a house being pulled by a team of horses across Gardner Lake. The ice sheet covering the surface of the lake may have been measured by drilling into the ice right by the shoreline. Unfortunately, the ice thickness was probably not consistent along the line the house was to be moved along, meaning the ice was probably thinner at the point where the house started sinking at 250 feet into the lake. Interestingly, the United States Army Corps of Engineers provides a table for mobile loads on varying thicknesses of freshwater ice – and their safety. Obviously, the standard of two inches thick of ice for a person to safely skate on, such as Gardner Lake, is much different to ten inches thick ice for a seven- to eight-ton truck driving over the surface of the ice. It is worth noting that unlike a single person skating or a vehicle driving across the ice, a house being pulled by a team of horses is considered to be a stationary load. What is fascinating about the ordeal is that while photos of the house teetering on the lake’s surface, partially submerged, it was memorialized in a color postcard.

Thomas LeCount, upon seeing his summer house parked in the lake, must have thought his original plan to be better, which meant moving the house on solid land. While this could not be done on the snow-covered ground, he might have waited until spring when the ground thawed out and was dry enough for an easy transition. LeCount moved to New York City with his wife, and according to his obituary in The Meriden Weekly Republican dated February 4, 1897, died at Roosevelt Hospital due to illness at the age of 48.

Image Credit: Tichnor Brothers, Publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.