The History of Persian Miniatures

As an ethnic art form, Persian miniatures not only have a rich history influenced by neighboring cultures such as the Byzantine and Hindu, but have also influenced many prominent western artists throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. According to an article from Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, NY dated February 9, 1930 Persian miniatures were first painted as illustrations for hand-printed books during the 11th century in what is now Iran. Derived from the Latin word “minium”, or red lead, due to the dominant color used in Persian paintings at the time, these miniatures became the hallmark of medieval Persian art. Once the new invention of paper reached Persia in the late eighth century from China, Persians discovered the substance was perfect not only for recording many oral traditions, but also for providing illustrations for the first books they made.

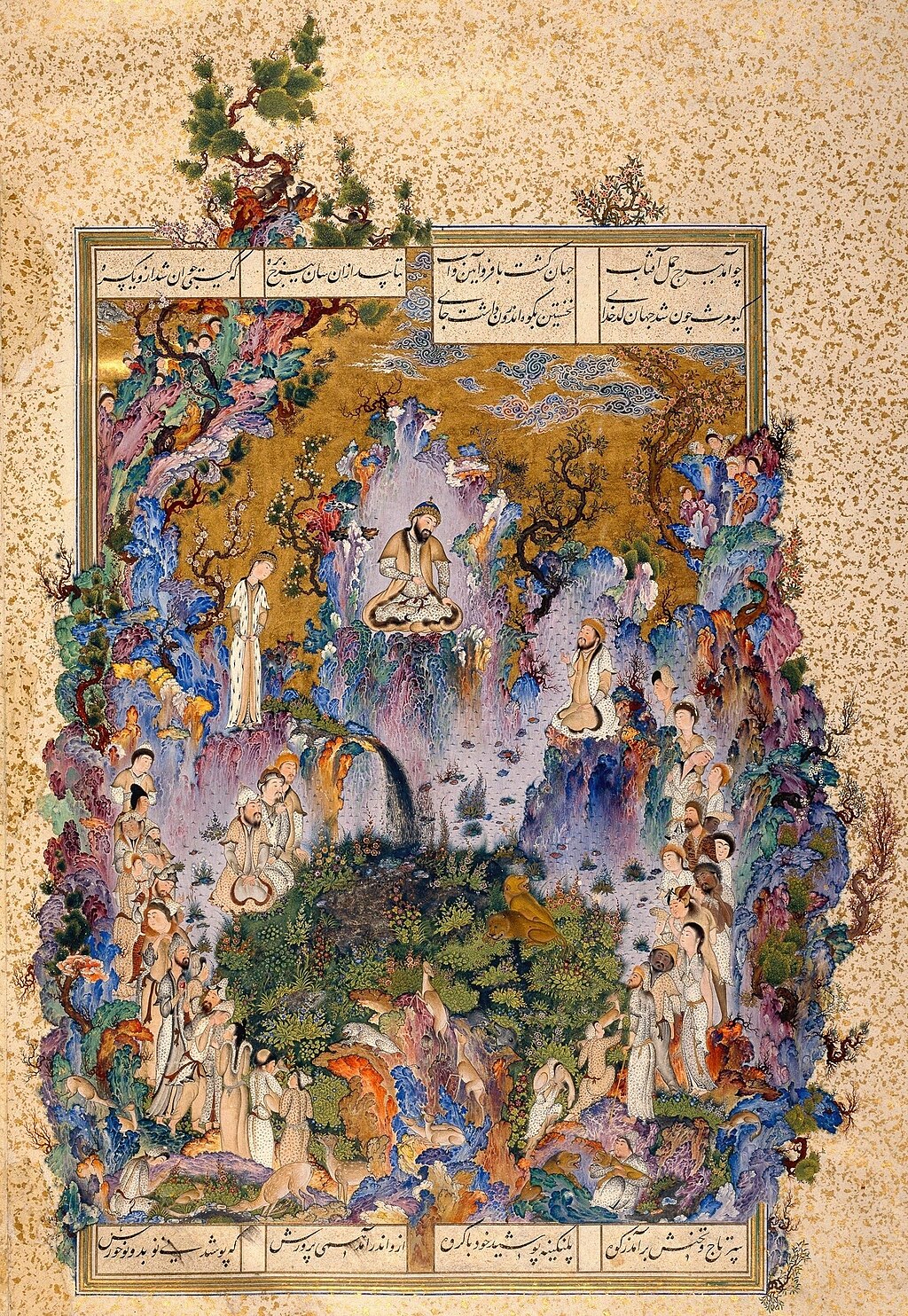

With no shortage of Persian literature from the late tenth century through eleventh century – the Shah Nameh, or Book of Kings by Ferdowsi being one of the most important works during this period – artists soon realized that texts of such magnitude deserved illustrations, often lavish ones consisting of pure, bright pigments with accompanying segments of Persian script written in narrow columns next to the illustration itself. One notable miniature from an early sixteenth century version of the Shah Nameh, “Kayumars Court” attributed to Sultan Mohammed, is one of the best-known examples of Persian miniatures, created under the rule of Shah Tahmasp by artists in the city of Tabriz in the mid-sixteenth century. The total number of miniatures in this particular printing of the Shah Nameh totaled 258. The complete manuscript was created with the intention to give to an important dignitary, Selim 2, the sultan of the Ottoman empire.

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that such a magnificent work of art would inspire both academics and the general art museum attendee to delve into the history of Persian miniatures and actively seek out other examples of this type of art.

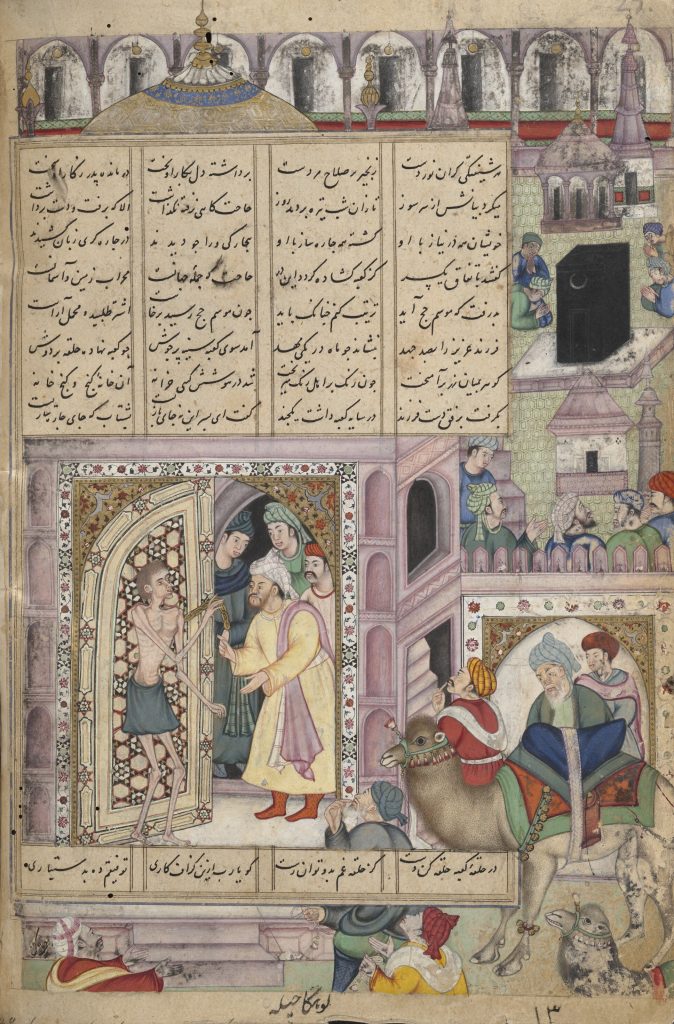

It is interesting to note that it is not unusual for Persian miniatures to bear images of animals and people, compared to the non-living images in the art of neighboring Arabia, a nation which relies upon geometric form and elaborate calligraphy. Nonetheless, this calligraphy is also echoed to a degree in Persian miniatures, which often contain one or more panels in an image containing Persian calligraphy text, usually from classic literature.

The very first Persian miniatures ever painted had a strong Byzantine influence, with the human figures painted always showing full-frontal facial views with the human figure being dominant. Between the eleventh and twelfth centuries, this slowly changed to incorporate more animal figures, and by the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries, more highly detailed works which established Persian miniatures as a national art form. Miniatures painted during the fourteenth century often depict historical elements, such as the Moguls in Persia.

Influenced by Chinese art brought to Persia by the Mughals in the sixteenth century, nature scenes became the background for the majority of Persian miniatures, with elaborate landscapes often becoming the primary focus while human figures and animals often became secondary. Also in the sixteenth century, Rajput art, native to India, had elements which started to blend with Persian miniatures, once the latter was introduced to India through the descendants of Tamerlane’s armies. In fact, by the seventeenth century, the vast majority of India art resembled Persian miniatures so closely that only an expert on the subject could discern if the work of art was actually made in Persia – or India. As with the Persian miniatures, paintings of important persons, events, hunting, and other outdoor activities were conveyed through the vibrant colors often used in these paintings. Human bodies are always painted in a fluid manner, striking poses with their arms and legs which seem impossible to replicate for an art model. Of course, paintings of building interiors included houses complete with walled gardens in Persian manuscripts, showing daily life taking place. Other primary examples of miniatures are: “Khusraw Observes Shirin Bathing” from the Five Treasures by Nizami Ganjavi, which depicts only two human figures a man and a woman, two horses, and an elaborate nature scene where the woman is pathing in a body of water; “Dancing Dervishes” from the Divan by Hafiz, the work of art attributed to Kamāl al-Dīn Bihzād. Here, a large number of people against an outdoor setting, dancing gracefully, with their bodies moving fluidly through space.

Persian miniatures in books have been compared to the illuminated manuscripts of western Europe, according to an article in The Hartford Courant dated May 14, 1961. Celebrated Persian painters like Bizhid, Mir Ali, and Muin Mossavar knew how to blend the colors seamlessly in their works of art, such as green, purple and brown in mountains which formed the background in many a miniature. Even the paintbrushes they used sometimes had only one or two hairs for such detailed work on creating individual faces of people in addition to outlines of the human body. Such artists made these miniatures come to life, the combination of nature with heroes and heroines which seem to be able to tell a story all on their own even without the need for the Persian text which often appears in these paintings.

Other major works of Persian literature which received a set of miniatures in their volumes include: Conference of the Birds by Farid ud-Din ‘Attar; Vis and Ramin by Fakhruddin As’ad Gurgani; Gulistan by Sa’adi; Laila and Majnun by Nizami; and Kalila and Dimna, which story originated in India, was translated into the Persian and Arabic languages in the seventh and eight centuries, respectively.

Persian miniatures are also used in modern books of poetry. Perhaps the most notable one is The Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam. Different published versions of The Rubaiyat usually come with their own set of miniatures and are sought after collectors of this very book. For example, the 1952 printing by Doubleday & Company in Garden City, New York, contains illustrations by Edmund Dulac on glossy pages, while the 1947 printing by Random House, New York, contains illustrations by an unidentified artist. In the 1947 book, each page contains golden-hued borders of animals and florals. The Rubaiyat was first translated into English from Persian by Edward FitzGerald in 1859 and consist of quatrains attributed to Omar Khayyam (1048–1131).

As an influence on western art, Persian miniatures have their share of admirers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is no accident that the British textile designer William Morris created fabrics, tapestries, and wallpapers that look like they sprang from the pages of a sixteenth-century Persian miniature, particularly those with ornate frames containing vines, flowers, and animals. Being a great admirer of this art form, Morris had endless inspiration to work from, which made him one of the most popular creators of art for the home during the nineteenth century. Today, the William Morris & Company still creates home furnishings utilizing many archival creations by Morris himself.

Perhaps it is because Persian miniatures are so unique in origin, with the noted Byzantine influences behind it, that they have been admired by so many people throughout the sixteenth to twenty-first century. Needless to say, these miniatures hold an important position in the study of world art, with only the rarest surviving works being housed in art museums or private collections. There are whole books devoted to the subject of Persian miniatures, which are essential for anyone who plans on studying or learning about the Middle East or India.

Image Credit: Persian miniature of a standing woman, 18th century. Smithsonian.