History of the Eddystone Lighthouse

Situated on a reef of eroded rocks nine miles off the southwest coast of Cornwall, England is a lighthouse which seems to have its base swallowed up by the North Atlantic Ocean when viewed from a distance. Considered a feat of engineering for its time in the year 1698, the Eddystone lighthouse has a fascinating history of its own. This lighthouse was originally built to help prevent ships from ramming into the Precambrian gneiss rock reef and causing sinking disasters. To date, four versions of the lighthouse have occupied this very spot, earning the Eddystone lighthouse a significant place in popular culture, with multiple books written about it, famous novelists mentioning it, even a pop-music group naming themselves after this famous landmark.

But power and art, ‘gainst furious storms combine,

Winstanley shouts, “the victory is mine!”

-Michael Rough

The very first lighthouse to be built upon the Eddystone reef was the Winstanley Lighthouse. It took two years to be built with work commencing in 1696 and finished in November 1698. This lighthouse was octagonal in shape, designed by Henry Winstanley, and built from wood. However, the wood used was nowhere near durable nor steady, and after the first winter during its existence, required external repairs. The new exterior was no longer wood but rather a 12-sided shape, or dodecagonal, stone structure. The top section remained an octagon where the main light was lit for ship captains to see. This octagon had eight windows installed. When Winstanley and five other men were working on the lighthouse, the Great Storm of 1703 hit, destroying the lighthouse, with all men inside drowning. Casualties of this extratropical cyclone were around several thousand lives, causing damage to England, particularly along the nation’s coast.

After the Winstanley Lighthouse was gone, a second one was erected in its place. The reef was leased to Captain John Lovett, who commissioned John Rudyard to design a lighthouse that would be more resistant to the waves and frequent winds. Built of wood, this lighthouse was more conical in shape, its total height, 92 feet. The structure was anchored to the reef with wrought-iron bolts in order to secure it in place. The top section of the lighthouse was octagonal in shape, where the lantern was held. Unlike the previous Winstanley lighthouse, the new one was far more durable and existed for fifty years from its date of completion, 1709. By 1715, Lovett died, and the new lease was purchased by Robert Weston, Rudyard, and another man. In December of 1755, a fire originating from the lantern broke out in the lighthouse. The lighthouse keeper, Henry Hall, along with the two other men present, tried to put out the fire but were unsuccessful. As the lighthouse proceeded to burn from the roof downwards, the wooden structure quickly went up in flames. Much to Hall’s misfortune, as he was throwing buckets of water on the spot of origin, the lead from the lantern roof melted and headed straight down towards his face, causing an accidental ingestion. Henry Hall died three days later from the molten lead hardening in his stomach.

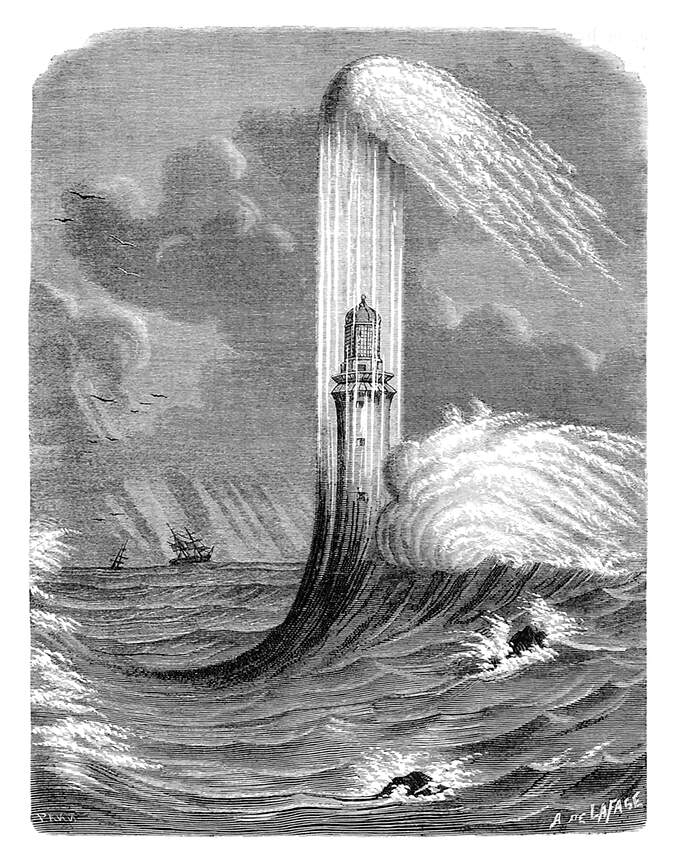

The Smeaton lighthouse, as shown in the accompanying illustration with this article, was built in 1759 by John Smeaton, a civil engineer employed by Robert Weston who was the owner of the former Rudyard lighthouse. The exterior was made with Cornish granite, the interior, with Portland limestone, which helped make the lighthouse secure on the reef when the waves came crashing against it. For reinforcements, a special type of concrete lime was used to adhere the lighthouse directly to the reef underwater, in addition to the granite blocks being secured together with the use of dovetail joints and marble pegs. At its complete height, the lighthouse was 59 feet high, with a base diameter of 26 feet. The top of the lighthouse was 17 feet in diameter, and its structure was formidable compared to the previous wood-based lighthouses.

Moving in to the nineteenth century, modifications were made to the Smeaton lighthouse, and a renovations done in 1841 to reinforce and strengthen it. These renovations include repointing, the replacement of water tanks, and filling in a large hole between the reef and lighthouse foundation. In 1845, a catadiopric optic was installed inside the top of the lighthouse, which used prisms instead of the old mirrors which proved to be more effective in reflecting light. This was the first time such a device was used in a lighthouse. Throughout the middle of the nineteenth century, the lighthouse was painted with broad red and white stripes on the exterior to increase visibility to sailors during daylight, and a fog bell was also included. While the improvements proved useful, it was determined that an even newer lighthouse be put up in place, and the existing Smeaton lighthouse dismantled and relocated to Plymouth Hoe, in the town of Plymouth, England.

In place of the Smeaton lighthouse, a new lighthouse was built upon the Eddystone reef: the Douglass lighthouse. Designed by James Douglass, this lighthouse is still standing today. Built of granite and standing 161 feet tall, it was completed in 1882, a fog bell was included, along with oil lamps, and a hexagonal biform rotating optic, each side bearing two Fresnel lens panels. This high-powered light source made it possible for ships as far as 17 nautical miles, or 20 miles away to see it. Before the turn of the twentieth century, an explosive fog signal device was installed, and just over sixty years later, an electric light was installed. By 1982, the lighthouse was automated, and moving in to the twenty-first century, it operated on solar power – a fully modern lighthouse.

In popular culture, the British pop band Edison Lighthouse took their name from Eddystone, best known for their melodic top-ten 1970 hit, “Love Grows (Where My Rosemary Goes)”. Herman Melville mentions the lighthouse in “Moby Dick” (1851) more than once. The British composer Ron Goodwin dedicated the opening and closing of his masterpiece “Drake 400 Suite” to Eddystone lighthouse. These are just a handful of the many references to the famous landmark in popular culture. Some of the books written about the Eddystone lighthouse include: “Henry Winstanley and the Eddystone Lighthouse” by Adam Hart-Davis (2002); “The story of John Smeaton and the Eddystone lighthouse” (1876) which contains stunning full-color illustrations of the lighthouse; “The Eddystone light-house, a poem” by Michael Rough, 1823; and “A narrative of the building and a description of the construction of the Edystone Lighthouse with stone” by John Smeaton (1791). Many other books dating from the late eighteenth century have mentioned in detail the engineering behind the lighthouse, such as “Recueil de divers mémoires” by Pierre Charles Lesage (1810), in French. Given the Eddystone lighthouse’s history, it is one lighthouse that can be appreciated in many ways, from its engineering to modern paeans.

Image Credit: By Amilcar de Lafage. From the book “Les merveilles de la science, vol. 4”, Louis Figuier. Published by Paris: Furne, Jouvet et Cie, 1870. The Getty Research Institute, The Internet Archive. From Old Book Illustrations.